Arabic

During my scholarship stint in Egypt it happened to know a foreign course attendee who had previously been in China to learn the language; one day, in Cairo, he looked discouragingly at me, and after a deep sigh, he said: “You know what? Arabic is more difficult to learn than chinese language…

Yes, Arabic language looks quite eerie to a westerner eye as it envolves three distinct difficult aspects: reading, writing and pronouncing it; and to learn it properly, without forgetting the words in a matter of months you have to write it – from right to left – by hand too.

I was though advantaged by my Sicilian origin which presents in its dialect many words of arabic origins and by my father who, when he was young, had been for almost ten years in Libia. Another link which I had inconsciously deemed as having distant relations to my DNA, was the fact that Cairo had been founded in 969 by the sicilian born warlord Jawhar As-Sahili: Sicily had been conquered beginning from 827 AD, in a span of more than a century, by the Fatimid empire.

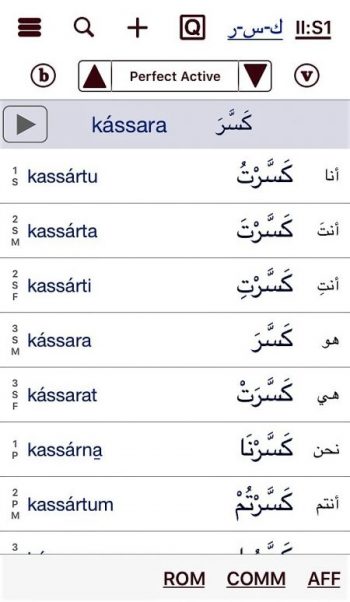

But let me give you a note of optimism: Arabic was very difficult to learn some decades ago; today, instead of laboriously squinting your eyes on the Hans Wehr traditional paper dictionary you can speed your learning with Apps, like the Cave Arabic Verb Conjugator. It has a steep price, but after having used it for many months, I can still say that buying it was worth all that money. Once you download the app – which weighs some 300 Mb – you can use it without connecting afterwards to the Internet.

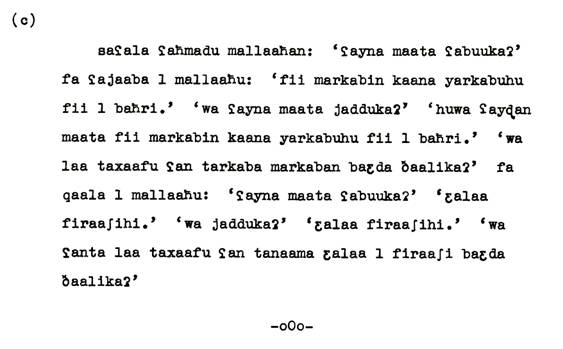

Arabic language it is based, as other Semitic languages – like Hebrew – on consonantal roots, most of them tri-consonantal.

On a traditional paper Arabic dictionary you will not therefore find the words in alphabetical order, but according to their roots, that is, the first form of the third singular person of the Perfect Tense. In the same list you will also have the other verb forms – mainly up to the tenth form – which are linked together in a sort of mathematical meaning variation.

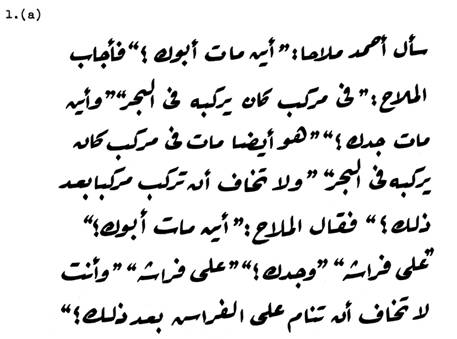

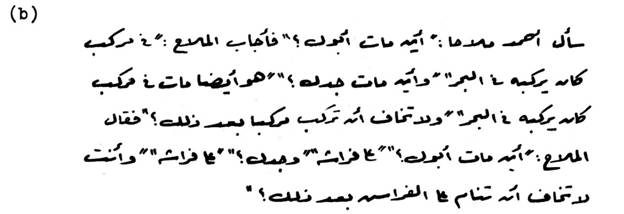

For example, Kasara, Perfect Tense first form, means to break – here by general agreement translated as Infinitive – while the second form, Kassara, which always represents an increasing of the meaning of the first form, means to smash. You will also have in that same list, the relevant substantives, adjectives, participles with prefix, and so on, such as: kisra (fragment, chunk, slice); Kaasir (ferocious); maksuurun (fragmented). A text sample has been posted hereunder, also in its cursive variation, coupled with its transliteration from Arabic, and its translation into English.

A note: on newspapapers you will not find in the words the vowels (three of them: a-u-i) which the reader will have to add; in other terms, as the word “newspaper” would appear “nwsppr”. But in the long run this will become very intuitive for the foreign reader as the process is ruled by a strict language sintax. Only old texts, such as the Coran, are vocalised.

The short tale below comes from the book ‘Writing Arabic’, by Terence Frederick Mitchell, Oxford University Press, which I bought at the time and found very useful; it’s still available at Oxford UP website with a steep price (£ 49). Hereunder I have also added the relevant Mp3, recorded in Cairo – while I was enjoying the afore mentioned scholarship – ‘starring’ Nabil, a cultured Egyptian friend of mine. The text is read by him twice; in the second one – referring to the handwritten sample – Nabil had increased his speed.

Sample of ‘Writing Arabic: A practical introduction to Ruq’ah script’:

Ahmad asked a sailor: Where did your father die? The sailor answered: “On a ship he was sailing on the sea”. “And when did your grandfather die?” “He, too, died on a ship he was sailing on the sea”. “And are you not afraid to sail a ship after that?” Then the sailor said: “Where did your father die?” “In his bed”. “And your grandfather?” “In his bed.” “And are you not afraid to sleep in a bed after that?”

***

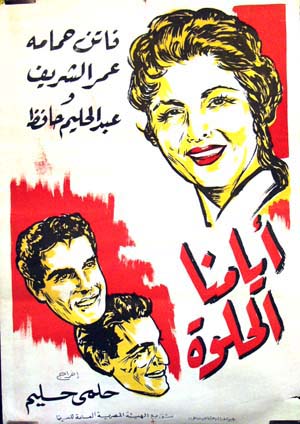

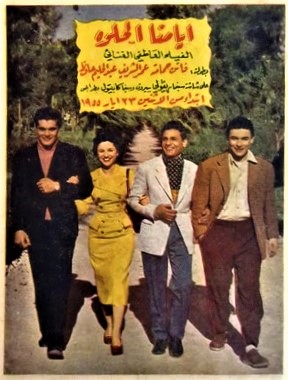

Below, the poster of the movie titled Ayyamna al-helwa, ( أيامنا الحلوة ) Our Best Days, 1955, Director Helmi Alim ( حلمي حليم ) and the leaflet of the movie, where, on its right side you can see a young Omar Sharif (عمر الشريف) whose interview made by me in Cairo can also be read here.

The main actor were: Abdel Halim Hafez (عبد الحليم حافظ ), actress Faten Hamama ( فاتن حمامه ), and Ahmad Ramzy (أحمد رمزي ).

On the poster on the left, as also on the movie leaflet on the right, you can see samples of the attractive calligraphy in Ruq’ah (or Riq’a) style, which is one variety of the Arabic script.

|

|

Hereunder two smartphone screenshots of the Cave Arabic conjugator above related to two forms of a verb: kasara and kassara – to break and to smash.

|

|

*****

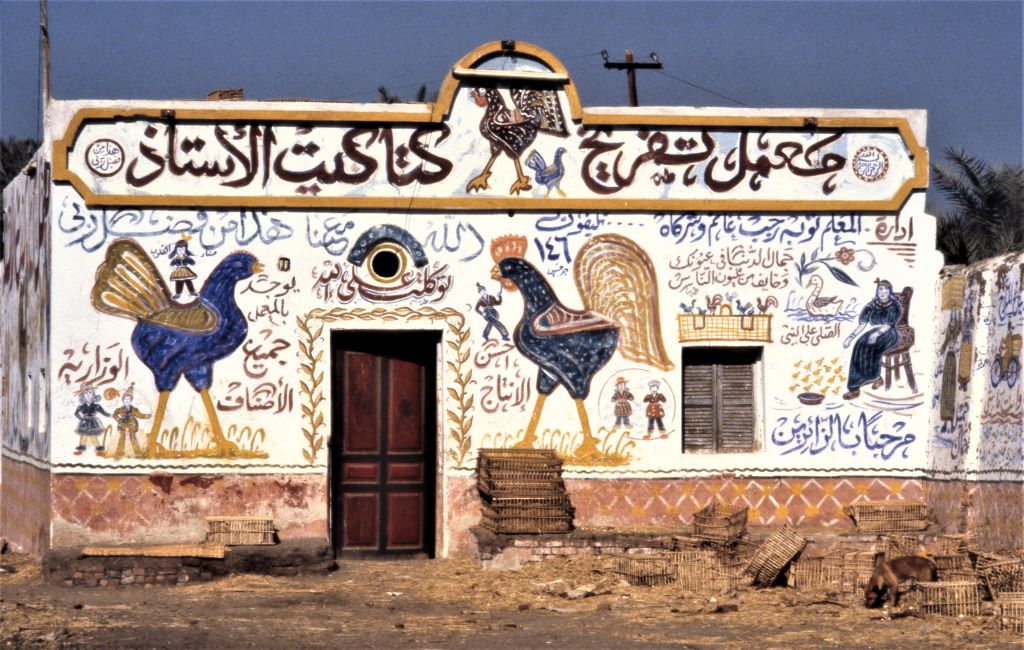

One day, in the winter of 1980, while travelling to Port Said I stopped by the roadside in a place called Wazariya, in the middle of the Delta Nile. The reason was because I had seen with the tail of my eye, while speedy driving my Fiat car, a squat building decorated with colourful nice graffiti. It looked like a billboard about a household chicken farm.

This Egyptian mural presented a big top title inside a frame divided by an imposing rooster and a strolling hen. On the two opposite corners you can see two circles with inscriptions inside. So, let’s go to discover the meaning of all the legends appearing on this mural where the style of calligrapy used is Arabic Ruq’ah, that is the one used for handwriting:

All the big title: Professor’s Chicks Breeding Farm مَعْمَل تَفْريخ كَتاكيت الاستاذ

Inside left small circle of the frame: This was possible because of my Lord Almighty هذا من فضل الربّي

Inside right small circle:In the name of Allah, the Benificent, the Merciful بسم آللّه الرحمان الرحيم

Under the big frame we see on the left side of the building a marching big hen; near its right feet there are two children, supposedly the owners’ sons, as should also be the case for the little girl on top of the hen.

Above the small girl on the hen, again the motif: This was possible because of my Lord Almighty هذا من فضل الربّي while the catchphrase “The beacon of hearts” منار القلوب , surrounds the owners’ daughter;

Above the two owners’ sons we discover the name of the place: Al-wazariya – الوزارية ;

On the big hen’s right side: In this farm you will find all kinds (of poultry) – يوجد بالمعمل جميع الآصناف

Follows, above the door, the drawing of a big eye which, in every religion, simbolizes the everywhere presence of God; as a matter of fact the phrase “God is with us” اللّه معنا , sides the drawing, while under it “I’ve put (my trust) in God” – تَوكّلْتُ على اللّه , stresses even more the faith in God of this household farm owner. Appears also a telephone number, 146 – ١٤٦ , for supposedly placing orders to Ghirghis, a Christian Copt name.

In the last section on the right, from the top, the word Administration – إدارة is underlined; follows the name of the owner: The professor Nuba Ragib Ghanim & Partners – المعلِّم نوبة رجب غانم و شُركاه .

A compliment to the owner’s wife – The beauty of the World is in your eyes جمال الدُّنيا في عُيونك , is stressed by a rose bending towards the portrait of the woman who is feeding 16 hatchlings. And we get to know that this lady

fears the hex: And she is afraid of people’s eyes – وخاىف من عيون الناس

Under the floating duck: The prayer for the Prophet – الصلاة على النابي (actually here appears the contracted form of the word prayer: الصّلى ).

Of course – despite the woman’s fears – they have to sell their poultry, therefore she, in the end, welcomes the visitors: مرحباً بالزّائرين .